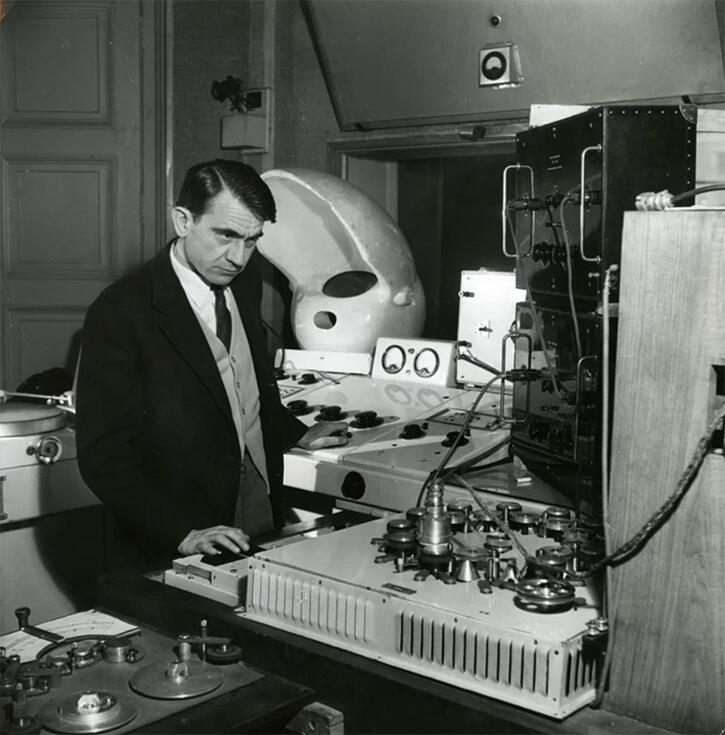

Pierre Schaeffer, known as the father of musique concrète, was a multifaceted figure whose influence extends far beyond his relatively small catalog of compositions. Beyond being a composer, writer, and radio technology pioneer, Schaeffer revolutionized the way music is created, heard, and understood, laying the foundations for many modern recording and sampling techniques.

Early Life and the Birth of a New Musical Approach

Schaeffer studied engineering, graduating from Paris’ École Polytechnique (1931), Supélec, and Télécom. His engineering skills were crucial for his musical experiments. In 1934, he began working in telecommunications in Strasbourg, but his interests soon shifted toward radio broadcasting and music, where he combined technical expertise with a passion for sound.

By 1942, Schaeffer had founded an experimental studio at the French National Radio, marking the start of his groundbreaking research. In 1948, he produced the first musique concrète works, including Études de bruits (Studies of Noise). He experimented with recorded sounds, playing them backward, slowing them down, speeding them up, and combining them in ways previously unknown. Using phonographs, early tape recorders, and record players, Schaeffer challenged the fundamental limits of musical expression.

The Concept of Musique Concrète

The term musique concrète was coined by Schaeffer in 1948. He believed that traditional classical music begins with abstraction (musical notation), which is later converted into audible music. Musique concrète, by contrast, starts with “concrete” sounds derived from natural phenomena and then abstracts them into composition. This approach disrupted conventional concepts of instruments, harmony, rhythm, and even music theory itself.

The importance of musique concrète can be summarized in three aspects:

- Inclusion of any sound in the musical vocabulary, initially focusing on unconventional instruments and later abstracting even familiar sounds.

- Manipulation of recorded sound to create musical works, using techniques such as tape looping and splicing, made possible by postwar technology.

- Emphasis on the “jeu” (play) in music creation, reflecting free improvisation with electroacoustic sounds.

Establishing Institutions and Theoretical Work

In 1951, Schaeffer founded the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC) at the National Radio, providing a laboratory for all forms of musical experimentation. In 1958, the GRMC was renamed Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM). This organization challenged conventional definitions of music, listening, timbre, and sound while conducting ontological research.

Schaeffer also established the research department of the Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française (ORTF), which he directed from 1960 to 1975, later becoming the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA).

His theoretical contributions were as significant as his compositions. In 1952, Editions du Seuil published his book In Search of a Concrete Music, summarizing his working methods. In 1966, he published the monumental treatise Traité des objets musicaux (Treatise on Musical Objects), formalizing his ontological studies.

Collaboration and Notable Works

Schaeffer collaborated closely with percussionist composer Pierre Henry, producing significant works such as Symphonie pour un homme seul (Symphony for One Man) (1949–1950), later choreographed by Maurice Béjart and performed worldwide in 1955. Their joint work, Orphée 51 ou Toute la lyre, was the first staged piece to combine voices, instruments, and magnetic tape.

Other notable Schaeffer compositions include Étude aux allures, Étude aux sons animés, Étude aux objets (1958–1959), Le trièdre fertile (1975), and Bilude (1979).

Legacy and Influence

Pierre Schaeffer is considered one of the most influential experimental, electroacoustic, and later electronic musicians. His innovative recording and sampling methods are now standard in modern music production, establishing him as a major precursor to contemporary sampling techniques. He was among the first to use recording technologies creatively and musically, inspired by Luigi Russolo.

Schaeffer also mentored a generation of influential musicians, including Éliane Radigue and Jean-Michel Jarre, who called his teacher the first DJ. His work was recognized with numerous honors, including an honorary membership at the Faculty of Arts at Tel Aviv University (1982) and the McLuhan Prize in Montreal (1989).

Although Schaeffer briefly returned to composition in the late 1970s, he devoted most of his later career to communication networks research and literary work. Nonetheless, his legacy—rooted in his revolutionary approach to sound, institutional development, and profound theoretical writings—continues to shape and inspire musicians and sound artists worldwide.

For readers interested in the evolution of computer-based music, it is worth exploring the work of Max Mathews as well. Often called the father of computer music, Mathews developed groundbreaking programs for digital sound synthesis, live performance tools, and electronic instruments that complement Schaeffer’s pioneering experiments with musique concrète. Together, their innovations laid the foundations for modern electronic and electroacoustic music.