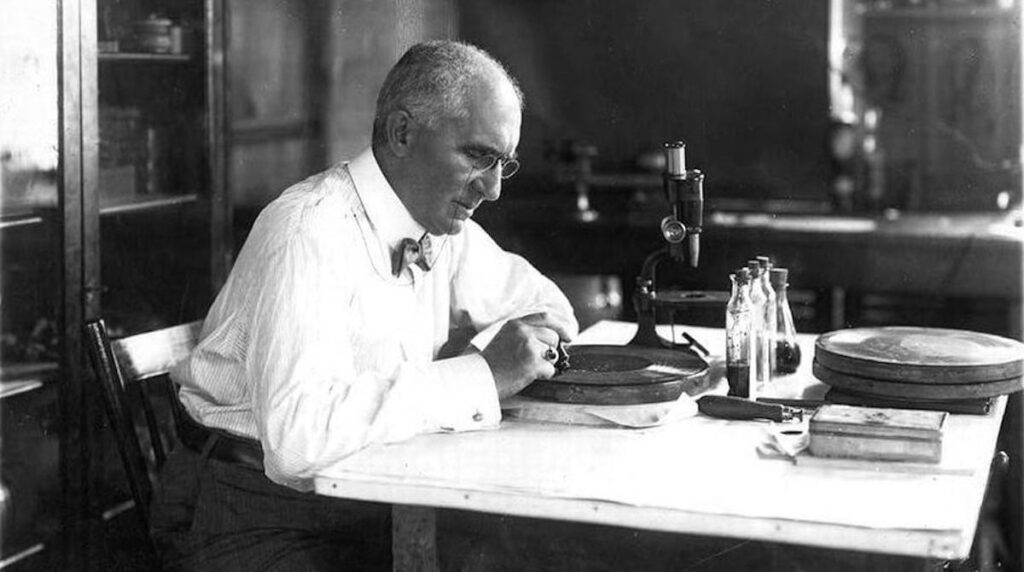

Although he has been overshadowed in the public imagination by contemporaries such as Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison, the German-American inventor and entrepreneur Emile Berliner (1851–1929) made two key inventions that transformed both telecommunications and the recording industry, making the musical experience preservable and suitable for the masses.

Early Years and First Successes

Emile (originally Emil) Berliner was born in Hanover, Germany, on May 20, 1851. His father was a merchant and Talmudic scholar, and his mother was an amateur musician. Berliner’s formal education ended in 1865 at age fourteen after graduating from the Samsonschule. In 1870, he emigrated to the United States, partly to escape military duty. Arriving in Washington, D.C., he began working as a clerk in a dry-goods store. During his first weeks in Washington, he added the “e” to his name, becoming Emile, to Anglicize it. He later self-studied acoustics and electricity. He became a U.S. citizen in 1881.

After the demonstration of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone in 1876, Berliner became interested in the device, finding that the transmitter needed improvement to make the product viable. in 1877, Berliner developed and patented a practical “loose-contact” transmitter (a type of microphone). This invention significantly increased the volume of the transmitted voice. In 1878, he sold his patent to the Bell company for $50,000. Berliner was retained as a consultant by Bell, but resigned in 1883 to devote himself fully to researching sound recording and reproduction. Notably, had Berliner taken shares in the Bell Telephone company instead of cash, their value would have reached $1,086,000,000.00 by 1986. In 1881, he also helped his brother Joseph found a factory for telephones and microphones in Hanover (J. Berliner Telefonfabrik), which played a significant role in introducing the telephone to Germany.

Invention of the Gramophone: The Path to Permanent Music

Berliner began working on improving Thomas Edison’s “talking machine” (the phonograph), which used foil or wax cylinders and vertical incising. Berliner concluded that wax cylinders were too soft and fragile, wore out quickly, and were unsuitable for mass production.

His main innovations involved using the disc format and the lateral (side-to-side) recording method:

1. Lateral Incising (Side Writing): Berliner utilized the method first suggested by Leon Scott de Martinville, where the stylus vibrated side-to-side in the groove. This “side writing” differed from Edison’s “depth writing” and allowed for improved sound, expanded sound range, and simplified duplication.

2. Durable Medium: Berliner initially experimented with cylinders wrapped in paper coated with lampblack. Further experiments in 1887 led to the use of 11-inch diameter glass discs coated with lampblack.

3. Etching and Permanence: Berliner developed a process to transfer the recording onto a flat zinc plate using photoengraving or, later, chemical etching. This process made the medium significantly more durable compared to the vertical incising method used on wax cylinders.

4. Mass Production: The invention of a method to create a negative copy (matrix) using electroplating. This matrix allowed him to stamp thousands of identical positive copies onto materials like celluloid, hard rubber, and later, shellac. The ability to mass-produce discs was key to the gramophone’s commercial success.

On November 8, 1887, Berliner was granted U.S. patent 372,786 for the “Gramophone”, which outlined his method of lateral recording and sound reproduction. He filed for a German patent (D.R.P. 45048) the same day.

Commercial Development and Legacy

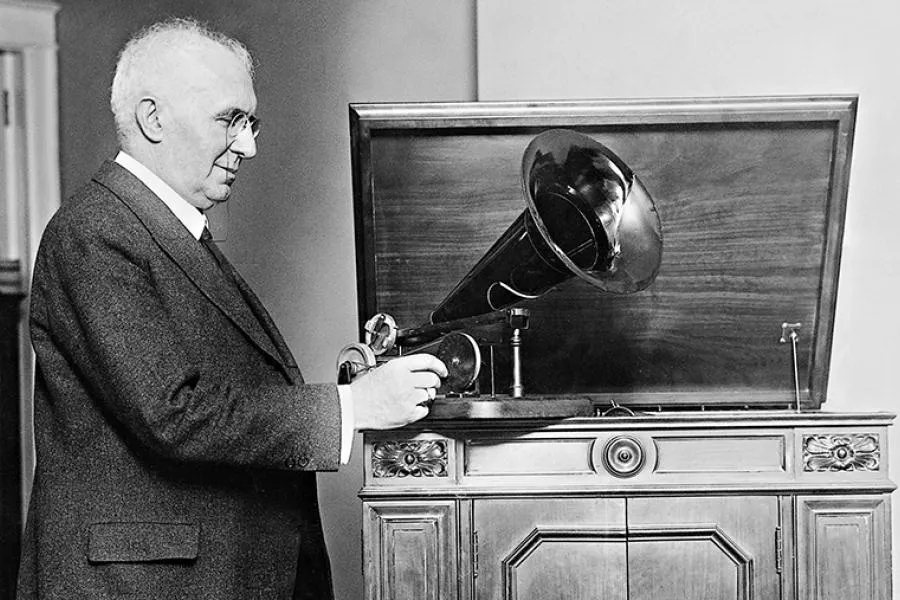

Berliner’s new direct acid-etching process had its first public exhibition at the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia on May 16, 1888. In 1889, Berliner secured a licensing agreement with the German firm Kämmer & Reinhardt, a doll manufacturer, to market a hand-driven toy gramophone and 5-inch discs. This initiative was successful, reportedly selling some 14,500 gramophones and an estimated 100,000 records of some 600 titles in 6 languages.

After returning to the U.S., Berliner founded the Berliner Gramophone Company in Philadelphia in October 1895. He switched from hard rubber (which tended to flatten) to a shellac mixture for the records in 1897. He also worked with Eldridge R. Johnson to manufacture gramophones with spring motors.

In the late 1890s, Berliner faced unfair competition. His exclusive U.S. sales agent, Frank Seaman, betrayed him by forming the rival Universal Talking Machine Company, which produced the Zonophone. In June 1900, a court injunction forced the Berliner Gramophone Company of Philadelphia to cease operations.

Berliner passed his patent rights to Eldridge R. Johnson, who founded the Victor Talking Machine Company (the forerunner of RCA Victor), in which Berliner retained a financial interest. Berliner subsequently moved his primary operations to Canada, where the Berliner Gram-O-Phone Company of Canada was incorporated in Montreal in 1904. The term “gramophone” remained in widespread use in Canada, while in the U.S., Edison’s preferred term “phonograph” eventually dominated.

Permanent Legacy

Berliner’s disc, initially played at 78 revolutions per minute, remained the standard technology for sound reproduction for almost 100 years, until digital formats began to dominate the market in the 1980s. The lateral incising method invented by Berliner is still used in vinyl records today.

Beyond sound recording, Berliner remained an active inventor in many fields:

• Aviation: He developed designs for early helicopters/gyrocopters and a lightweight internal combustion engine. His son, Henry, was a pioneer of helicopter flight in the U.S..

• Acoustics: He patented acoustic tiles made of porous cement to improve acoustics in concert and lecture halls.

• Humanitarian Work: He was a great philanthropist and an active figure in public health. He funded an infirmary building at a tuberculosis sanitarium and tirelessly advocated for the mandatory pasteurization of milk to reduce the high mortality rate among infants.

• Education Support: In 1908, he established the Sarah Berliner Research Fellowship in honor of his mother, providing support to American women pursuing PhDs or D.Sc. degrees in physics, chemistry, or biology.

Emile Berliner died of a heart attack on August 3, 1929, in Washington, D.C., at the age of 78. His life was dedicated to inventions that, through the gramophone and disc record, forever changed how the world creates, disseminates, and preserves music.

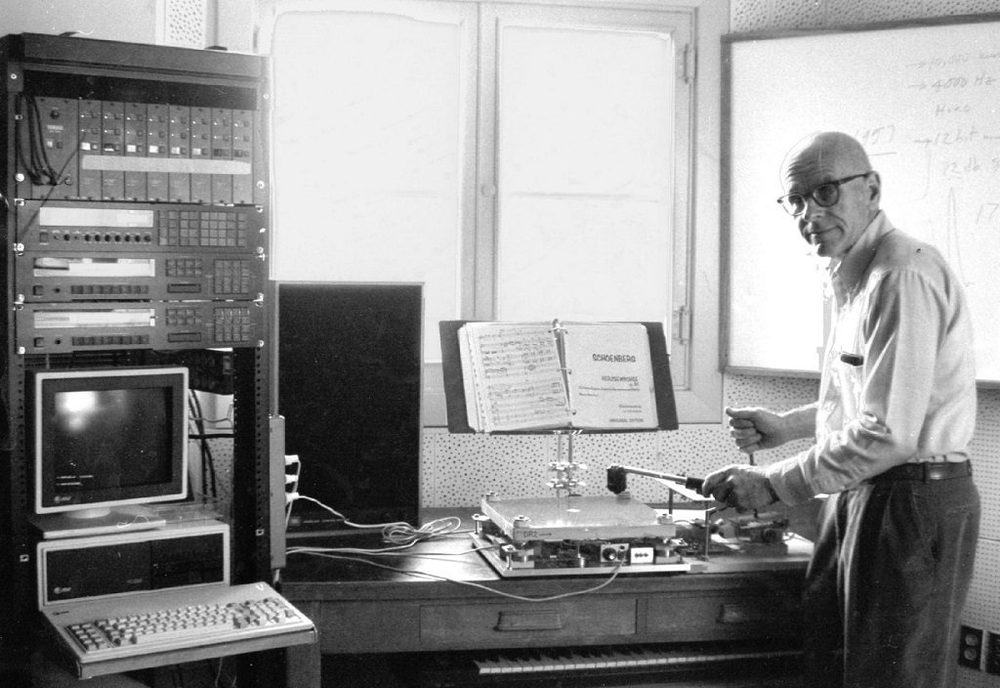

For those interested in the evolution of recorded sound into the digital age, learn about Max Mathews, the father of computer music.