In today’s world, filled with an endless stream of sounds, the question of whether silence truly exists is becoming increasingly relevant. Is silence merely the absence of sound, or is it an active state we perceive? How does music, which is itself a form of sound, coexist with the concepts of noise and noise pollution? These questions are explored in numerous works that study the philosophy of sound, the history of music, and the impact of noise on our lives.

The Elusiveness of Silence

Silence, as a concept, is central to the philosophy of sound. Salomé Voegelin’s book Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art contains chapters on “Conceptual Silence” and “Radiophonic Silence,” as well as reflections on the idea that “when there is nothing to hear, you start hearing things.” This underscores the notion that absolute silence may be unattainable, and that even in the absence of external sounds, our inner hearing becomes active.

Luigi Russolo, in his manifesto The Art of Noises (1913), argued that “ancient life was all silence,” and that “noise” only emerged with the rise of machines in the 19th century. He believed that before this moment, the world was quiet, interrupted only by natural phenomena such as storms, waterfalls, and tectonic activity. These sounds, however, were neither as loud, prolonged, nor varied as those produced by industrial machinery. This perspective suggests that silence was the natural state before the industrial age.

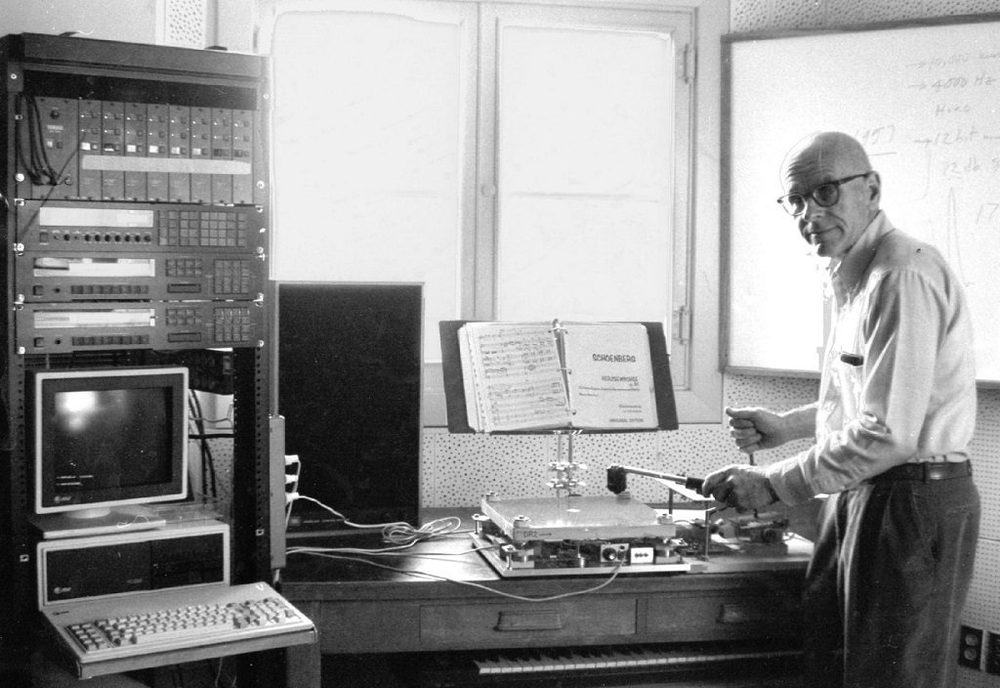

John Cage, the American experimental composer, authored Silence: Lectures and Writings (1939–1961), a collection of essays and talks exploring the nature of silence and its role in music. His famous composition 4′33″, consisting of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of “silence,” forces listeners to hear the ambient sounds of the environment, demonstrating that silence itself is filled with presence.

Damon Krukowski, in Why Sound Matters, highlights the “dwindling quiet places” of the modern world, emphasizing that silence, once more common, is now becoming a rare and valuable resource.

Music and Noise: Interaction and Transformation

The relationship between music and noise is both complex and dynamic. Jacques Attali, in his book Noise: The Political Economy of Music, argues that music, as a cultural form, is closely tied to the mode of production in any society. He identifies four cultural stages in the history of music: “Sacrificing,” “Representing,” “Repeating,” and “Post-Repeating.”

- During the stage of Sacrificing (before 1500 CE), music opposed the “noise” of nature — death, chaos, and destruction — serving as a means to preserve and transmit cultural memory.

- In the era of Representing (1500–1900 CE), as music became a commodity, it turned into a spectacle. Silence in concert halls became the expected condition for performances, giving music its autonomy. Attali notes that the “ideal silence that greeted musicians created music and gave it autonomous existence, reality.” This established a divide between performers and audiences, turning music into a monologue of specialists before consumers.

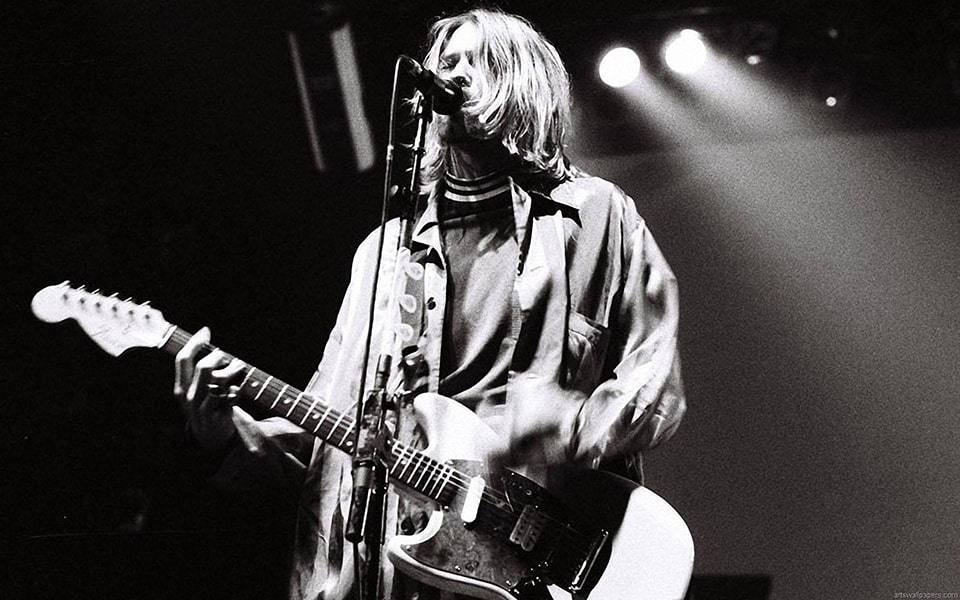

- In the age of Repeating (1900–present), linked to recording and broadcasting, music shifted toward fidelity — the perfect reproduction of recordings. Creativity became defined by how precisely a performance could replicate the “original.” This process, Attali argues, stripped music of much of its social and political power.

Russolo, one of the most influential theorists of 20th-century musical aesthetics, maintained that the human ear had adapted to the speed, energy, and noise of the urban industrial soundscape. He urged musicians to explore the city “with ears more sensitive than eyes,” listening to the wide spectrum of noises often taken for granted yet rich in musical potential. Russolo proposed incorporating “noise-sounds” into music, categorizing them into six families: roars, whistles, whispers, screeches, percussive blows, and voices of animals and humans. In his view, music should expand the field of sound, replicate the endless timbres of noise, and free itself from tradition by exploring diverse rhythms.

Contemporary Sonic Landscapes

Krukowski also draws attention to the destructive impact of noise pollution, particularly in deep-ocean ecosystems. He notes that urban attempts to reduce noise have often led to greater isolation, loss of community, and a sense of physical disconnection from the environment. He further reflects on the consequences of sound’s commercialization in the digital era.

By contrast, David Toop in his book and compilation Ocean of Sound explores ambient music as a form of deep mental engagement. He defines ambient music as both a source of relaxation and as a medium that “taps into the disturbing, chaotic undertow of the environment.” Rejecting the idea of background music, Toop emphasizes the immersive quality of musical experience in the 20th century. His compilation blends dub, exotica, free jazz, and field recordings, beautifully illustrating the ideas of his book.

Conclusion: Towards Sonic Sensibility

The question of whether silence exists in the modern world has no simple answer. While absolute silence may be an illusion, the very concept continues to shape how we perceive sound and music. Increasing noise pollution and the commercialization of sound threaten our “quiet places” and our ability to listen in new ways.

Music — from ritual acts to commodified performances to ambient experiences — continually redefines its role within this sonic environment. The philosophy of sound art, as studied by Salomé Voegelin, encourages us to explore listening as both an aesthetic and philosophical practice, cultivating sonic sensibility. This sensibility is crucial for rethinking our relationship with sound, noise, and music, helping us “hear the world anew and restore our connection to one of our most precious natural resources.”

For further insights into how sound environments interact with cultural contexts, see The Impact of Architecture and Environment on Music Genre.